It seems web users might be more easily influenced than we think. A fascinating study by Professor Thorsten Joachims and his team at Cornell University shed light on how people interact with search engine results pages (SERPs). Their research revealed a significant tendency for users to click on the very first listing far more often than its actual relevance would suggest – highlighting the powerful influence of default options.

Initial findings, consistent with previous studies, showed that a whopping 42% of users clicked the top search result, while only 8% opted for the second one. This isn’t entirely surprising, as we know top positions generally attract the most attention.

However, the truly insightful part of the study involved a clever manipulation. The researchers secretly used a script to swap the order of the top two search results before they were displayed to users. So, the listing that was originally second now appeared first, and the original top result was moved to the second position.

Even with this swap, the results were striking. Users still clicked the new top entry 34% of the time, while the new second entry received 12% of the clicks.

The Magnetic Effect of the Top Spot

This experiment helps us understand why the top result gets so much attention. There are two main possibilities:

- Search engines are incredibly accurate at determining relevance and almost always place the best result first.

- Users click the top result simply because it’s at the top. This could be due to laziness (we naturally start from the top) or because users assume the search engine has correctly identified the best option.

The study’s findings indicate that the truth lies in a combination of both factors.

If users were always clicking the best link, then swapping the top two should have also swapped the click percentages. But this didn’t happen; the top spot still commanded the most clicks.

Conversely, if users blindly trusted the search engine and clicked the first link solely because it was first, then swapping the order shouldn’t have changed the percentages at all. This also wasn’t the case. The click-through rate of the top link decreased from 42% to 34%. This means that 8% of users shifted their clicks: 4% clicked the second result (which was originally first), and another 4% explored other options further down the page.

To further understand the accuracy of the search engine’s rankings, the researchers had human evaluators judge the relevance of the websites. Since there’s no definitive way to objectively determine the “best” website for a given query, they averaged the ratings of five individuals – likely the most reliable method for assessing information relevance.

The evaluation revealed that the original top result was judged the most relevant only 36% of the time, while the second result was deemed most relevant 24% of the time. Interestingly, the two top results were considered equally relevant 40% of the time. This shows that while the search engine was often correct, it was wrong about one-fourth of the time. (When the top two are equally relevant, the placement doesn’t really matter, so these instances were counted as “correct.”)

Considering how often the search engine’s top pick wasn’t actually the most relevant, users clicked it far too often. And when the top two were switched, too few users adjusted their behavior. The clear conclusion is that there’s a significant bias towards clicking the top link, although the quality of the link does still play a role.

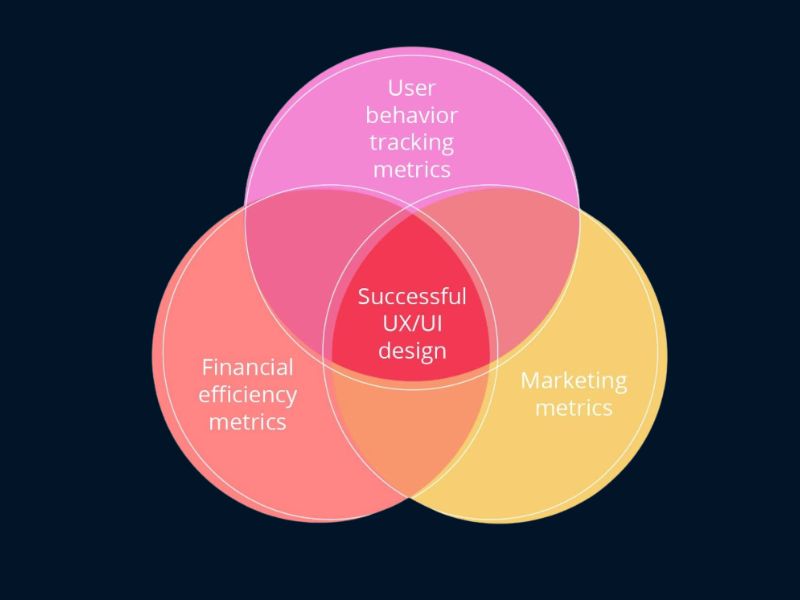

For search engine marketers, the implications are clear: achieving that top spot is incredibly valuable. However, it’s equally crucial to have compelling “microcontent” – like effective page titles and summaries – that increases the likelihood of users perceiving your site as relevant. Unfortunately, controlling these snippets can be challenging on major search engines like Google, which often displays unhelpful and unclear descriptions. You have more control over this for internal search engines on your own website or intranet, assuming you can encourage content creators to write good summaries.

Defaults Extend Beyond Search

The power of defaults isn’t limited to search results. Users frequently rely on pre-selected options in various aspects of user interface design. For instance, they rarely delve into complex customization features, making it essential to optimize the default user experience, as this is what most people will stick with.

In forms and applications, pre-filling fields with the most common value can significantly improve usability. For example, on a conference registration form, if someone registers for the New York event, the country field could default to “United States.” If they register for the London event, it could default to “United Kingdom.” While users from other countries will need to change this, they would have had to specify their country anyway if the field was left blank. By using the most frequent value as the default, we save many users a small amount of effort.

Defaults offer two key usability benefits:

- By presenting a representative value, they act as just-in-time instructions, helping users understand how to complete a field.

- By showing a frequent value, they provide insight into the commonly expected response, as opposed to less typical ones. This knowledge can even be used for sales purposes – for example, by pre-selecting a one-year subscription option over a monthly one. However, consistently defaulting to the most expensive option can erode trust, so it’s important not to overdo it.

By guiding and informing users, well-chosen default values help reduce errors. Therefore, it’s crucial to select defaults that are genuinely helpful, rather than simply choosing the first item alphabetically or whatever happened to be at the top of an initial list.

Reference:

Thorsten Joachims, Laura Granka, Bing Pan, Helene Hembrooke, and Geri Gay, “Accurately Interpreting Clickthrough Data as Implicit Feedback,” Proceedings of the Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR), 2005. (Note: The link leads to a PDF file, which is an academic paper.)

This article has been edited from Nielsen Norman Group with the title The Power of Defaults by author Jakob Nielsen.